Dance Is Evidence: Rethinking History Through the Moving Body – Gandhara, Buddhism, and The Greeks

This article is adapted from a talk I will give at the Third International Academic Conference on the Buddhist Heritage of Pakistan, in Peshawar and Islamabad, on 27–31 March 2026, where I will present as the Chief Dance Advisor to Dr. Ijlal Hussain, Director of the Silk Road Centre in Islamabad.

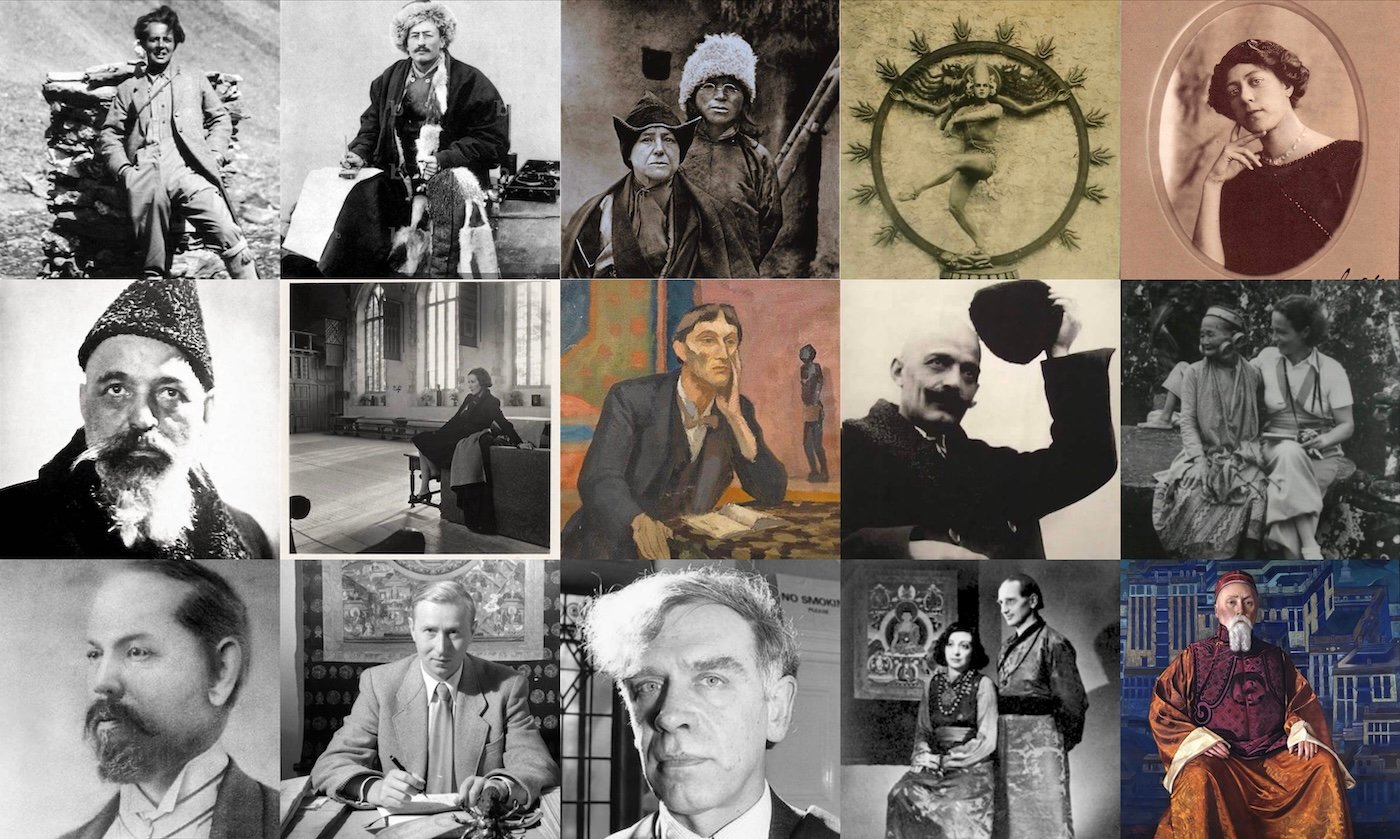

Image courtesy of the author

Dionysian Bacchanalia, Gandhara, first century CE. Schist. Image courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art

Histories of Buddhism are usually written with texts, monuments, and philosophies. Movement, despite being ubiquitous in Buddhist life, has rarely been granted the same status. Dance, when it appears at all, is often treated as ornament, performance, or cultural byproduct rather than as a source of knowledge.

Yet, what if dance is not a mere embellishment of Buddhist history, but one of its most precise forms of evidence?

This question arises with particular force in Gandhara, the ancient cultural region centered in what is now northern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan. Gandhara is perhaps best known for its striking Buddhist sculpture, its monastic complexes, and its role as a cultural and commercial crossroads for South and Central Asia. It is also the homeland of two major Buddhist thinkers—Asanga (fl. fourth century CE) and his half brother Vasubandhu (4th–5th century CE)—whose work would shape Buddhism across Asia for centuries. Gandhara also contains Swat, home of the legendary dancing wizard, Padmasambhava, who established Tantric Buddhism in Tibet.

Yet Gandhara was not only a landscape of texts and stone. It was a region alive with disciplined movement: ritual walking, formal postures, hand gestures (mudra), processions, circumambulation, warrior dances, and sophisticated theatrical forms, all shaped by centuries of cultural exchange across vast distances. When we look at Gandhara through the lens of movement, a different history begins to come into focus

Buddhism as a practice of the body

A helpful way to approach this is to set aside, for a moment, the idea of Buddhism as a “religion” in the Western sense. As the scholar and classical dancer Vena Ramphal has observed: “Buddhism is more accessible when understood as a practice of mind and body—as a movement practice—than as a system of belief; religion is probably the wrong word.”

This perspective aligns closely with the Yogacara school of Buddhism, developed in the fourth and fifth centuries by Asanga and Vasubandhu. Yogacara—often translated as “mind-only” or “practice of yoga”—is deeply concerned with how perception is formed, conditioned, and transformed. Reality, in this view, is not passively received but actively constructed through habitual patterns of structured cognition.

What is often overlooked is that Yogacara’s insights are inseparable from embodied discipline. Sitting postures, controlled breathing, walking meditation, circumambulation around stupas, and the precise use of gesture were not peripheral to Buddhist life; they were foundational. The body was trained so that perception itself could change.

In this sense, Yogacara does not give us dance manuals or choreographic notation. Instead, it gives us something more fundamental: a grammar of metaphysical movement. It establishes that liberation—understood here not as salvation, but as a transformation of how reality is apprehended—is procedural, conditioned, and enacted through practice. Once that is recognized, ritualized movement becomes not optional but inevitable. It is interesting to consider the mind-only teachings of the Yogacara school as the inner condition for later Vajrayana Buddhism’s outward tantric expressions, such as cham. The inner dance is primary, generative, and remains as an outer dance takes shape in a vortex.

Young men continue to perform the Attan today. Peshawar. Photo from Core of Culture

Gandhara as a culture of movement

Gandhara was uniquely positioned for such developments. From at least the fourth century BCE onward, the region absorbed Hellenistic influences following the campaigns of Alexander the Great and the subsequent Indo-Greek kingdoms. Greek artistic and theatrical traditions did not vanish quickly; they persisted, adapted, and mingled with local forms for centuries.

Greek culture, often mischaracterized as purely intellectual, was in fact deeply somatic. The Greek exaltation of the human form in art is unparalleled. Philosophy was paired with bodily discipline (Gr: askesis), ethics with habituation (Gr: hexis), and metaphysical insight with ritual enactment. The Greek gymnasium was where the body was trained, cleaned, fed; and where the mind was exercised through philosophical debate, and where teachers taught. The human form was a manifestation and embodiment of Greek ideals and virtues. Famously, the Greeks exercised naked in the same place where they debated philosophy.

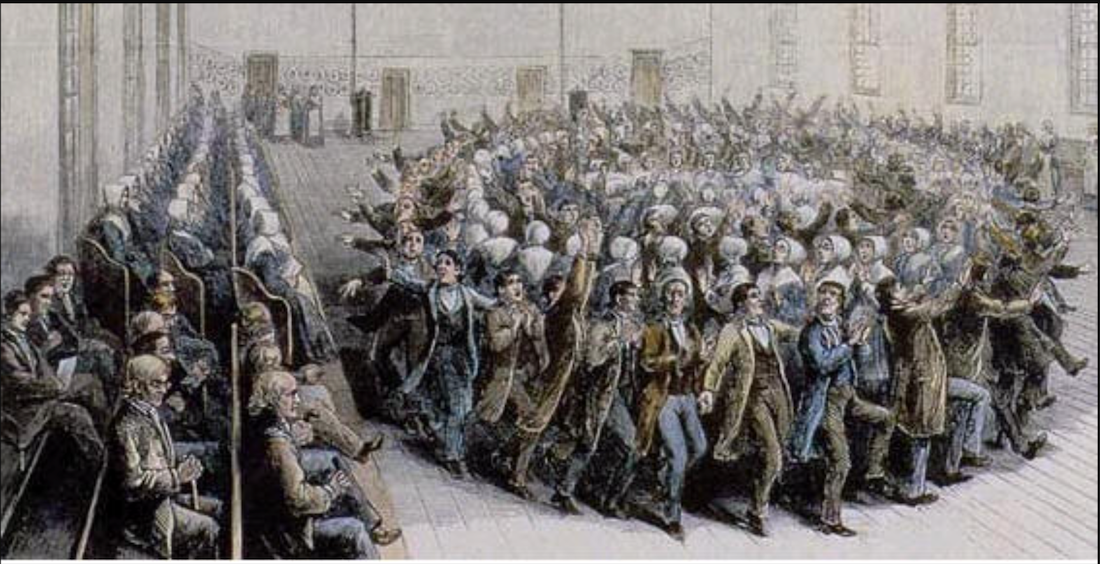

Greek tragedy relied on the chorus: a collective body with no individual identities moving rhythmically through space and mythic history to make cosmology, ethics, and human suffering intelligible; to deliver moral teaching. They danced to chanted poetry. The first great tragic poet, Aeschylus (c. 524–456 BCE), was a general in the army. The annual performances of tragedy was a contest in honor of Dionysus. The Greek god Dionysus appears in multiple art forms and places within Gandhara. The ancient ritual Dithyramb, upon which tragedy was developed, was practiced and depicted in stone reliefs in Gandhara. Dancing Bacchic ecstatic rites, called Bacchanalia, are depicted in multiple places in Gandhara.

These Greek ideas of the mind-body complex did not arrive in Gandhara as abstract doctrines. They arrived as ritualized drama. These ideas arrived in the bodies of trained performers—as ways of standing, walking, gesturing, dancing, and occupying architectural space; ways of chanting, singing, shouting, and acting. Gandharan Buddhist sculpture bears this out: contrapposto stances, flowing drapery, rhythmic groupings of figures, and processional compositions all reveal a visual logic rooted in Greek ritual movement, and notions of the body. The Buddha is a muscular hero in Gandharan sculpture.

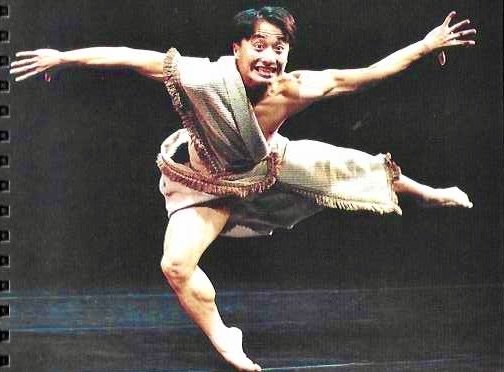

At the same time, the region was home to indigenous traditions of martial and ecstatic dance, including Pashtun warrior dances such as the Attan, characterized by rhythmic stamping, circling, spinning, and collective intensity. These Afghan dances were not entertainment; they trained martial skills—endurance, focus, cohesion, courage—and the experience of moving powerfully with an elevated consciousness. The Attan is still performed today. It is nearly 3,000 years old. It is a culturally foundational movement expression that has not lost its relevance or power. The longevity of certain ancient dances is worth investgating.

In Gandhara, then, indigenous ancient mountain dance traditions, Buddhist monastic practice, and Greek theatrical embodiment of myth coexisted within the same cultural milieu. The story is not simply influence in one direction, but convergence: a shared understanding among different cultural traditions that the body is a primary instrument of knowledge. This is a story of ongoing cultural interaction and integration among movement practices over a long period.

Standing Boddhisattva, Gandhara, 2nd–3rd century CE. Schist. Private Collection. Image courtesy pf the author

Reading Gandharan art as a movement archive

When viewed through this lens, Gandharan art reveals new dimensions. A standing Buddha image with a raised hand is not merely an icon; it preserves a repeatable bodily configuration—balanced weight, upright spine, deliberate gesture—designed to organize attention in both practitioner and viewer. A seated Buddha in meditation depicts choreography reduced to stillness, where internal movement replaces external motion. It has been claimed that the image of the Buddha seated with crossed-legs in meditation—showing his calm body as vessel of enlightenment—originated in Gandhara.

Narrative panels showing devotees circumambulating stupas capture cognition in motion: structured walking, rhythmic repetition, cosmic parallels, and spatialized thought. Even Buddhist guardian figures such as the Boddhisattva Vajrapaṇi—often modeled on the Greek Herakles (Hercules) in Gandharan sculptures—display coiled energy and controlled force, anticipating later ritual dynamism. The interaction of these separate movement cultures developed mind-body training to endow the body to mean; to take on and embody profound meaning.

Cham dancer, protective deity, Punakha, Bhutan, 2005. Photo by Gerard Houghton. From Core of Culture

From Yogacara to Vajrayana to cham

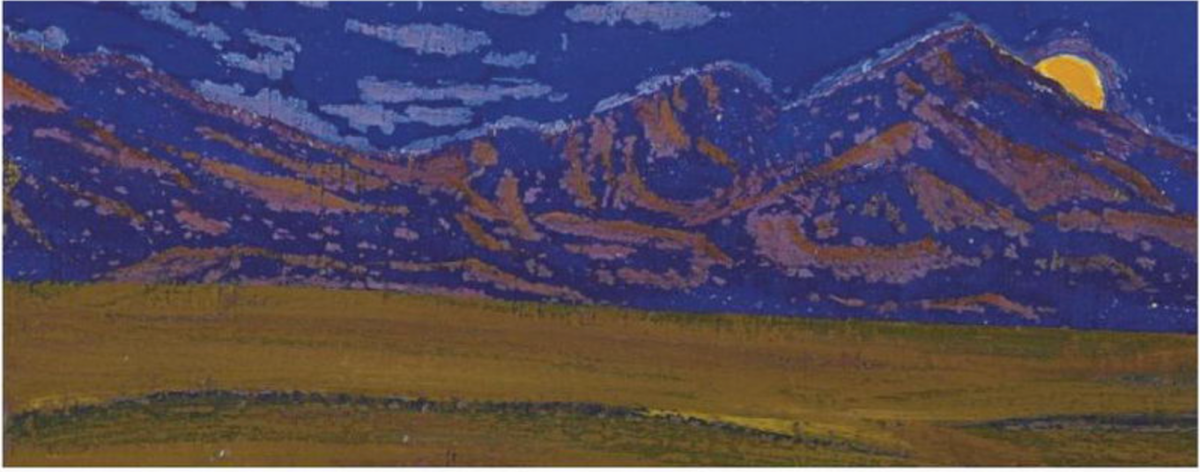

Seen this way, the later emergence of Vajrayana Buddhism appears not as a rupture, but as an intensification; a material manifestation of inner reality. The eighth-century master Padmasambhava, traditionally associated with the Swat region of Gandhara, brought together Yogacara’s analysis of perception with explicit ritual technologies of embodiment taken from traditions of dance, magic, tantra, and wizardry from throughout Central Asia and the Himalayas. Greek ritual dance and cosmology were integrated with local artistic patterns. It was a cosmopolitan milieu of mind-body techniques.

Visualization practices became performative. Gestures and postures became empowered. Movement itself became a means of transforming reality—not symbolically, but operationally, for both the dancer and the devoted observer.

The masked ritual dances known as cham—attributed to Padmasambhava and which flourish in Tibetan and Himalayan Buddhist cultures—represent the completion of this arc. Cham makes cosmology visible, ethics kinetic, and metaphysics communal. Doctrine is no longer only studied or contemplated; it is enacted, remembered through the body, and renewed in public space.

Nepal’s Kathmandu Valley offers a later and still-living example of such a milieu: an urban pilgrimage landscape where ancient yogic ritual, Tantric Buddhism, and daily embodied practice have long been interwoven. Read alongside Gandhara, it suggests that the transmission of Buddhist thought has often depended less on linear dissemination than on the emergence of fertile social ecologies of practice. From this dance perspective, figures such as Padmasambhava appear not as solitary innovators moving through empty space, but as catalysts working within—and between—places already primed for yogic and ritual synthesis.

Padmasambhava did not invent movement in Buddhism. He completes a long historical process in which the body—in its true power—gradually comes fully into view. Padmasambhava’s historical significance lies not only in what he taught but where he taught. It helps sometimes to think of Padmasambhava not as an historical person embarked on mythic wanderings, but as a connective intelligence, a situational intelligence at thresholds of creativity. Moving from Gandhara to Kathmandu and then to Samye in Tibet, is Padmasambhava moving among hotbeds of yogic evolution. Nothing random; self-selecting perhaps. Dance is a manifestation of that evolution, from Swat to Kathmandu to Samye. Miracle of miracles: these dances still exist.

Curatorial ethics and the present moment

Treating dance as evidence carries responsibilities. When living traditions are presented to the public—whether on festival stages, in museums, or in scholarly writing—choices must be made about naming, framing, and alteration.

Calling dances by their proper names, resisting the urge to simplify or aestheticize them for international audiences, and allowing forms to speak on their own terms are not political gestures. Dances should be shown for what they are, not as mascots for globalist tropes like “world peace.” For example, call the dance Attan, not Pakistani folk dance. Don’t change the way the Attan is performed when showing it to foreigners to try to suit their taste. Show the Attan for what it is. Rearrange the audience, not the dancers. These are methodological commitments. If movement is a historical source, it deserves the same care we give to texts or artifacts. We don’t change them to make them simpler; we learn how to read and appreciate them. This approach might be called curatorial ethics: an awareness that how we present embodied knowledge shapes what can be known about it.

Recognizing dance as evidence does more than add a new topic to Buddhist studies. It shifts the ground of inquiry. It reminds us that history is not only written—it is walked, gestured, rehearsed, and remembered through the body as dance. For Gandhara, this perspective restores a missing dimension. It allows us to see the region not only as a crossroads of ideas, but to see Gandhara as a laboratory of embodied knowledge, the influence of which continues to move—quite literally—across Asia. Dance, in this sense, is not an accessory to history. It is one of its most articulate witnesses.

A dancing maenad, in a trance, in a Dionysian ecstatic ritual, c. 325 BCE, at Paestan, Greece. From wikimedia.org

See more

Core of Culture

Related features from BDG

Ancient Dances TodayEarly Explorers and Their Encounter with Buddhism, Part Three: Dance InsightThe Attan

Related news reports from BDG

Third International Conference on the Buddhist Heritage of Pakistan Now Accepting Abstract SubmissionsOrganizers Hail “Overwhelming Response” to Third International Conference on the Buddhist Heritage of Pakistan

More from Ancient Dances by Joseph Houseal

The post Dance Is Evidence: Rethinking History Through the Moving Body – Gandhara, Buddhism, and The Greeks appeared first on Buddhistdoor Global.