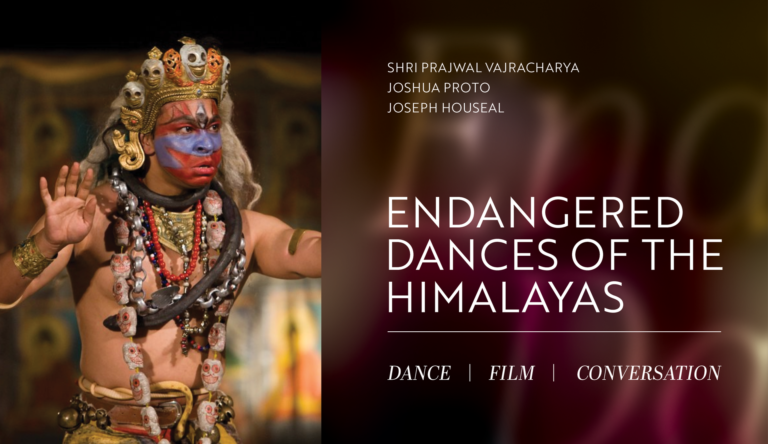

Guru Rinpoche and His Buddhafield of Tantric Dances

Guru Rinpoche and His Buddhafield of Tantric Dances

April 27, May 4, May 11, May 18 2025

2:30pm PST | 4:30pm CST | 5:30pm EST

90 minutes/ session. Live on Zoom.

All sessions are recorded and available for one year

Core of Culture Presents:

Guru Rinpoche and His Buddhafield of Tantric Dances

Re-establishing Dance in the Narrative of Padmasambhava

With Karen Greenspan, author, researcher, and dance writer, and Joseph Houseal, director of Core of Culture

Featuring original research, writing, photographs and video documentation of extant dance traditions associated with Padmasambhava /Guru Rinpoche, his Tantric identity, and the many dynamics he set into motion.

4 SUNDAYS:

April 27, May 4, May 11, May 18 2025

2:30pm PST | 4:30pm CST | 5:30pm EST

90 minutes/ session. Live on Zoom.

All sessions are recorded and available for one year

Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rinpoche, is revered as The Second Buddha, and the bringer of Tantric Buddhism to Tibet, where it flourished. Padmasambhava was an esoteric master and expert dancer, moving through dancing cultures and several extant dance traditions in Swat, Nepal, Bhutan, and Tibet.

Dance specialists Karen Greenspan and Joseph Houseal have dedicated decades of their lives to researching these dances. In this workshop course, Greenspan and Houseal connect the dances to the legends, the geography, the mysticism, and religious teachings associated with the larger than life character of Padmasambhava, and re-establish dance in the narrative of Guru Rinpoche.

Syllabus

WEEK ONE: Who is Guru Rinpoche?

Video opening – Guru Rinpoche, a figure of widespread devotion

Two great disseminators of Guru Rinpoche’s identity and characteristics. The structural creation of a legend/myth/buddha. The primacy of esoteric teaching above all.

– with Karen

The Lotus Born by Yeshe Tsogyal – The Life Story of Padmasambhava, introducing his many manifestations.

Guru Tshengye, The Eight Manifestations of Guru Rinpoche, a metaphysical schematic and a Cham performance structure.

Discussion:

Why is dance central to Vajrayana Buddhism? Quotes from the great masters on cham and dharma dance, dance intelligence, dance as metaphor, some thoughts about literacy, the ubiquity of dance, not mentioning what everyone knows, and the possible motives behind the creation of this 8-sided identity

WEEK TWO: The earthly travels of Padmasambhava

Dance traditions associated with Padmasambhava/Guru Rinpoche along this travel route:

Attan, Charya, Naked Dance, Cham.

– with Joseph

Swat – Padmasambhava’s choreographic milieu, — with Joseph

Nepal – Charya Nritya and ancient Vajracharyas. Padmasambhava’s practice of Vajrakila Tantra in the caves of Nepal, influencing his activities in Bhutan and Tibet,

– with Karen

Bhutan, Case Study: Nabji. Padmasambhava, Dorje Lingpa and the Naked Dance of Nabji. The creation of a Thangka painting depicting the dance legacy of Nabji

– with Joseph

Tibet – Samye – an Earth Ritual; Guru Rinpoche overcoming obstacles with Vajrakilaya Cham

Eight Charnel Grounds associated with Guru Rinpoche’s travels.

– with Karen

Charnel grounds visited by Padmasambhava and his tantric accomplishments in those sites.

– with Karen

Discussion:

Dance as evidence, as a moving aggregate symbol of meaning

WEEK THREE: Treasures, Treasure Revealers, Treasure Dances

The basic reflex of Treasure Revealers (terton) and their revealed treasures (terma).

Guru Rinpoche’s reincarnated disciples discover teaching meant for a later time. These include many dances. What is a Treasure Dance – tercham?

– with Karen

Mystical travel:

Zandok palri – Guru Rinpoche’s translucent palace of light in another dimension. Zandok Palri is generator of dances in another dimension. The role of Zandok palri in the mystical tradition – visionary meditation practices – of creating yogic dances. Artistic depictions of Zandok palri.

– with Joseph

Influential Tertons and the Extant Dances they revealed:

Guru Chowang – Guru Senge Cham

– with Karen

Pema Lingpa – the Ging Sum

– with Joseph

Karma Lingpa – Bardo Cham

– with Karen

Discussion:

How can westerners appreciate the long Buddhist tradition of the visionary origin of dances?

WEEK FOUR: Contemporary Buddhist Dance Practices and Guru Rinpoche

Far too many to name.

Dakini Cham

Tara Dances of Prema Dasara

– with Karen

Chogyal Namkhai Norbu – Vajra Dances, and the exhibition “Visionary Dance in Buddhism, Footsteps to the Divine” at the Museo di Arte and Culture Orientale, directed by Alex Sielecki.

– with Joseph

Concluding Discussion:

Dance evidence, dance research, and re-establishing dance in the narrative of Padmasambhava/ Guru Rinpoche

Materials and images will be made available in advance of each session through the Yangchenma student portal.

ABOUT CORE OF CULTURE:

Core of Culture educates the public, practitioners and scholars about disappearing cultural heritage. We are dedicated to safeguarding intangible world culture, and assisting the continuity of ancient dance tradition, and embodied spiritual practices where they originate, and beyond.